Introduction

Plants of the genus Adenium-commonly called Karoo rose, desert rose, impala lily, Sabi star, or simply adenium (not italicized or capitalized)-make superb collector's specimens whether maintained as dwarfs or grown into small trees. Both the swollen, twisted stems and large bright flowers are eye-catching. But despite their great beauty they are not very popular and are seldom grown to large sizes, even by succulent collectors. Adeniums have acquired an undeserved reputation for being slow-growing and temperamental. They are in fact fast-growing and easy to cultivate when given proper care. This article is devoted to detailing their cultural needs.

Nine taxa of these pachycaul shrubs or small trees were recently described in this journal and summarized in part 6 (Hanson and Dimmitt, 1996b). Whether regarded as full species or un-deserving of even varietal status (compare Plaizier, 1980, with Rowley, 1983), the taxa are distinctly different horticultural entities. Their differences must be recognized in order to grow them well. The cultural techniques and resulting performance described here are for seed-grown plants in containers in the semi-desert climate of Tucson Arizona, outdoors from April through October. Expect similar performance wherever comparable sun and warmth can be provided. Old, especially wild-collected, specimens should be treated much more carefully.

The Key to Success: They Aren't Desert Plants

A fundamental change in the prevailing perception about adeniums is necessary to grow them well. The common wisdom is that they cannot tolerate a good watering. I've seen many ten-year old plants only a few inches tall stunted by chronic water stress. The essence of this article can be summarized in two crucial rules: 1) Grow adeniums as wetland tropicals, not desert plants. 2) Reject rule #1 when the plants are dormant.

Watering

While some populations do grow in extremely arid deserts, it does not necessarily follow that they need to be wedged in a rock crevice and constantly deprived of water. Many xerophytes evolved from tropical species that adapted to aridity rather than migrated as the forest retreated due to climatic change. Adeniums are apparently among these, and most of the taxa have not lost their affinity for more mesic growing conditions.

All taxa (except possibly A.socotranum) respond to generous watering during warm weather. Treat them as if they were tropicals such as hibiscus or gingers and they will respond dramatically. This is especially true of many of the hybrids which exhibit great vigor. Keep the potting mix continuously moist during the active growth season. Root-bound plants may be watered almost daily in hot weather. Adeniums are planted as hedges in the Philippines and India, where they thrive on more than 60 inches (1500mm) of rainfall a year (Alfred B. Lau, Ashish Hansoti, pers. Comm.). The taxa that lack an obligatory dormancy (A.obesum and A.swazicum) can also be watered through the winter if they are kept warm (at least 80F, 27C days, 5OF, 10C nights), but let the medium become nearly dry between irrigations.

This is sufficiently important to justify repetition; Water them as if they were coleus or tomato plants while they're growing in hot weather, but as if they were delicate, rot-prone cacti during winter. Adeniums are extremely susceptible to rot when watered too frequently during cool weather or if chronically waterlogged at any season. Use of a well-drained potting medium prevents most rotting problems.

Adeniums require high light intensity, 5000 to 8000 foot-candles outdoors (full sun is about 10,000 fc in clear, dry air). They tend to grow spindly in climates with cloudy summers or if they receive sun less than half the day. In desert climates most taxa perform best in light afternoon shade (30-50%). Mature plants of all taxa can be acclimated to full desert sun, though only Adenium swazicum performs well in extreme heat. In cooler, cloudier, or more humid climates adeniums should be in full sun all day outside or with 4000-6000 footcandles under glass.

Keep the plant facing the same direction all summer. If the pot is rotated, intense sun can severely burn the formerly shady sides of the stems. Autumn is the most hazardous time, when the sun is low in the sky but still strong. The bases of young plants are especially sun-tender and should be protected from the sun of arid climates until they are at least three inches (7-8 cm) thick. When first put outside after winter storage, foliage may scorch. This is not serious; new, sun-adapted leaves will soon appear

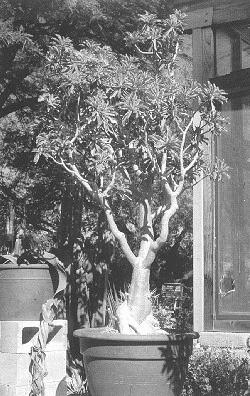

Fig.3. The same individual of 'Endless Sunset' as in Fig.1 at 13 years of age. It stands seven feet above the 30-inch pot, having added two feet in height in the preceding eight years plus a lot of stem thickening. |

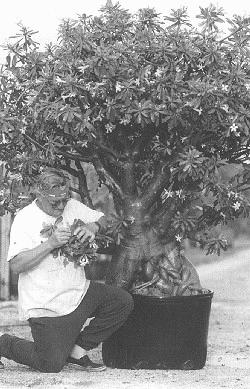

Fig.4. Adenium obesum ("Big Mama") filling a 45-gallon container at about 12 years of age. It measures 71/2 feet (2.3 m) tall from the ground and the exposed root-mass (caudex? See discussion of this species in Dimmitt and Hanson, 1991) is 34 inches (86 cm) wide. Grown by John Lucas (in photo) of Tradewinds South Nursery, Florida. |

|---|

Adeniums thrive during moderately hot weather (85-95F, 30-35C), preferably accompanied by moderate to high humidity. However, growth and flowering seem to be suppressed by temperatures consistently above 100F (38C). Plants grown outdoors in southern Florida (Jim Georgusis and John Lucas, pers. comm.), or in a greenhouse in southern Arizona, grow nearly year-round. The common factors in these two locations are moderately high temperatures and high humidity. Plants grown outdoors in southern Arizona begin vigorous stem-growth only after the monsoon (humid tropical air) arrives in July.

Dormancy is induced in all taxa when nights regularly fall below about 50F (10C). When completely dry and dormant they can tolerate near-freezing temperatures, though there is increased risk of root-rot below 50. Even a light frost will cause severe damage and usually subsequent death from rot to all adeniums except A.swazicum, which tolerates upper 20sF (about -2C) when dry and dormant.

Feeding

Adeniums also respond well to regular and generous fertilizing. I use slow-release fertilizer in my potting media and inject my irrigation water during the growing season with a balanced fertilizer such as 20-20-20 plus micronutrients at a concentration of 200 ppm nitrogen.

Inadequate watering and feeding are the primary reasons adeniums have been regarded as slow-growing. Generous culture produces literally unbelievable results. (An eight-month-old plant splitting a six-inch pot that I entered in the seedling category at a CSSA show was disqualified by the judges because they didn't believe it was less than the limit of a year old.) Specimens several feet tall and wide in 18-inch containers can be grown in only three to five years (Figs.1, 2) and sometimes even less.

Adeniums seem to require high nitrogen for both strong growth and copious flowering. For one year I used a low nitrogen fertilizer (2-10-10) on most of my mature adeniums in an attempt to thicken their stems while minimizing further elongation. Not only did the low-nitrogen plants not thicken appreciably, they also flowered poorly that year. (Well-fed plants flowered normally.)

Overwintering

Adeniums must be grown in containers in climates with frost or cool, wet winters. Adenium obesum, A.swazicum, and some of their hybrids, can be kept active by maintaining night temperatures above 50F (10C). The other taxa will enter various degrees of dormancy in autumn regardless of conditions.

Recognizing dormancy is critical to a plant's survival. Not only does the timing and depth of dormancy vary among taxa, but individual plants (even of the same clone) vary with cultural conditions from year to year. Dormancy is often signalled by a sudden yellowing and dropping of most or all of the leaves. Some weeks before this occurs you may notice a significant decline in water consumption. Either of these events demands sharply reduced watering.

There may be some shedding of older leaves near the autumnal equinox, apparently in response to shortening days. This event does not require less watering if the stems continue to grow new leaves. Partial defoliation may also occur at other times in response to a missed watering or a dramatic change in weather. As long as stem-tips are actively producing new leaves, keep watering normally.

Dormancy varies from complete defoliation (A.boehmianum and A.multiflorum) to just curtailment of stem growth (A.somalense and A.arabicum retain leaves if watered sparingly). Some taxa flower primarily during dormancy either with or without leaves (A.somalense and A.multiflorum, respectively).

If a warm sunny space is not available or if the plant is an obligate winter rester, reduce or stop watering when the nights regularly fall below 50F (10C) or when a plant signals onset of dormancy. Place in a dry, cool but frost-free location. Light is not essential to dormant plants, except that the winter bloomers will not flower normally in poor light. I have successfully overwintered mature plants of A.obesum, A.swazicum, and A.multiflorum under a carport, with no water, from November to April. I winter most of my large plants in an unheated and uncooled greenhouse in which temperatures approach 90F (32C) on sunny days and commonly dip below 40F (5C) at night. Under these conditions many plants continue flowering well into the winter, but they eventually shut down. This is colder than ideal and a few plants succumb to rot each winter.

Recognizing the end of dormancy is even more crucial. Root rot most often strikes in spring as a result of too much water too early; overpotted plants are most susceptible. The arborescent form of A.somalense from northwestern Kenya is particularly sensitive. On the other hand, adeniums will usually not leaf out if the potting medium is completely dry. Therefore I recommend watering sparingly through the winter (as little as once per month for large, leafless plants). Watch for expanding terminal buds in spring. At the first sign of activity increase the watering frequency gradually until the plants are in full growth.

Potting

Adeniums need ample root-space for rapid growth. Root-bound plants greatly curtail their growth even if watered and fed generously Plants should be repotted frequently until they attain their desired size. Plastic, porous clay, concrete, and stoneware pots are all suitable. But be aware that the massive roots of adeniums have no respect for expensive ceramic pots. Use thick-walled and preferably bowl-shaped containers to avoid breakage.

Potting mixes are more variable among growers and are the subject of more debate than any other horticultural topic. I will stress only two critical points here. First: The potting mix MUST provide excellent drainage and aeration if the plants are to survive the watering regime I recommend. Any medium that satisfies these criteria is at least satisfactory. Adeniums perform well in media ranging from 4:1 pumice : humus to pure Sunshine Mix #1 (which is mostly peat moss) and at pH values ranging from 5.5 to 8. Second: Each grower must experiment to find the potting medium that works well for him or her. Sorry, there is no better answer!

It is impossible to overemphasize the importance of experimentation. For example, several Tucson growers have concluded that the humus ingredient significantly influences performance. Adeniums and many other succulents perform superbly in media containing Sunshine Mix, Ball Mix, and coir (a peat-like product made of coconut husk) and poorly with several other brands. We don't know whether these results are due to the products or culture conditions; both vary greatly. It's a good practice to obtain several plants of the same kind and pot them in different mixes to determine the best one for your cultural conditions.

Repot during the active growing season, the earlier the better. Plants that have not filled the pot with roots by fall are much more likely to rot from an ill-timed watering. Do not water for a week or so after repotting if any large roots were damaged or if the weather is not warm and dry. If large roots have not been damaged, follow the tropical, nonsucculent model and water repotted plants immediately. Water stress can trigger dor- mancy which may not break until the following summer. Treating cuts with dusting sulfur and watering-in with fungicide are probably beneficial, though I rarely do so.

The plant can be raised above the previous soil line, exposing more of the caudex or succulent roots. Beware that newly exposed roots are susceptible to sunburn; they require a full growing season of gradually reduced shading to acclimate to full desert sun.

Pests rarely damage adeniums grown outdoors. Sometimes new leaves are deformed by an unseen pest in the growing tips (probably thrips or psyllids). Control requires a systemic insecticide; several applications may be necessary. Despite the extremely poisonous sap. rodents occasionally gnaw on roots and trunks.

Indoors mealy bugs, spider mites, aphids, and white flies often infest plants; all can cause severe damage. Use pesticides carefully, as adeniums are sensitive to some. Insecticidal soap and micro-encapsulated diazinon (Knox.Out) are safe for the plants (I make no claims for humans or pets). The systemic Dimethoate 267EC is not phytotoxic if used as labelled at temperatures below 90F (32C). Beware; Cygon has the same active ingredient but the "inert" solvent kills foliage.

Roots are susceptible to water molds (e.g., Pythium and Phytophthora) which thrive in waterlogged soils. Prevention is the best strategy because most fungicides are ineffective against this group and the few that are (e.g., Ridomil, Subdue, Banrot) are expensive. Use of a well-drained medium and careful watering prevents most root rot.

Warning; do not use any pre-emergent herbicide with the active ingredient oryzalin (e.g., Surflan) on adeniums or most other Apocynaceae (e.g., Plumeria, Pachypodium, Mandevilla, Macrosiphonia). A single application permanently arrests root growth and the plants slowly die. Oleander is the only member of the family tested that is unaffected (Dimmitt, unpublished data).

Etiolation (weak, elongated growth) is caused by too much water and/or fertilizer combined with too little light or poor air movement. This common problem is easily remedied by improving the growing conditions and pruning off leggy stems.

Care of Mature Specimens

When a plant reaches the desired size, reduce watering and feeding to slow further growth. Even in hot weather, adeniums maintain well on as little as two waterings per month. Hard-grown plants have leaves only at the stem tips, fully revealing their gnarled forms. While floriferousness may decline noticeably, hardened plants are more resistant to pests and diseases.

Propagation

Superior clones can be propagated by cuttings. Large hardened stems will root dependably but may take several months. I get the fastest results with either vigorous four- to six-inch (10 to 15cm) tip-cuttings or the next lower stem segment of semi-hardened "wood" dipped in liquid rooting hormone, and stuck in a coarse medium (e.g., perlite-vermiculite) under mist with bottom heat of 90-95F (32-35C). Under these conditions roots form in two to four weeks. Using a fungicide formulated against water molds reduces loss. Keep them well watered; cuttings that wilt usually fail to root.

Grafting is also an effective method of propagation, and it can also improve growth form. Spindly plants such as typical clones of A.swazicum become noticeably sturdier when grafted onto a stouter rootstock. Grafting is also useful for combining a superior flower with a caudiciform rootstock or for placing several flower types onto a single plant. Cleft-grafting of half-inch (1.25 cm) thick stems produces a smoother union than side-grafting. I've had greater than 90% success using actively growing rootstock; the scion may be dormant or active.

Growing from seed is easy though pollination is a challenge (Anderson, 1983) and seed cleaning is tedious. My success when using known compatible parents ranges from nearly 100% in some years to zero in others. Many clones seem to be either male- or female-sterile, and some rarely cross in either direction. After the follicles mature, remove the coma (tuft of hairs) at both ends of each seed before sowing.

Seeds germinate in about a week at 85F (30C). Treating with fungicide before sowing reduces loss. Seedlings of most taxa grow rapidly. They will usually keep growing through the first winter under tropical conditions and sometimes a second before obligate dormancy appears. Seedlings of several taxa and most hybrids will flower within a year or two, sometimes in as little as six to eight months. Adenium somalense crispum and multiflorum mature in about three and five years, respectively.

Producing Large Specimens

As is true of many plants, only young adeniums have a capacity for rapid growth. Production of large specimens requires pushing seedlings or small cuttings with generous culture during their first two or three years. Growth slows greatly in maturity; old plants can seldom be induced to resume vigorous growth. The 'Endless Sunset' in Fig.3 is eight years older than the photo of the same plant in Fig.1, so it attained most of its present size in its first few years.

Fear not that plants pushed in this manner will lose their character. Large plants with luxuriant foliage make lots of photosynthate, which in ma- ture adeniums is channelled largely into stem thickening. Don't compare adeniums with related Pachypodium species, which do indeed grow spindly weak stems when pushed, especially at high temperatures. I have grown the arborescent form of A.somalense to eight feet tall in two years from seed. In their third year they entered maturity in which flowering began, stem elongation slowed, and the main stems began thickening (Hanson and Dimmitt 1995). In their fifth year they are well on their way toward the "mini-baobab" form of wild plants. Growth form (i.e., tree or shrub) is genetically determined, while growing conditions during youth strongly influence ultimate size.

Addendum: After submitting this manuscript, I visited nurseries in Florida that are producing adeniums by the thousands. Their popularity seems to be on an upsurge.